The Flames of Rebirth: War in Fire Emblem Three Houses

During the summer of 2019 I bought myself a Nintendo switch, and a copy of Fire Emblem: Three Houses purely on a whim. I don’t normally buy games at launch, but I needed a first title for my new game system and had never played a fire emblem game before, so I decided to take the plunge. I finished my first play through of the game that fall, and by early 2020 I was working on my first maddening run, the hardest difficulty. Today I’ve completed the game front to back five times. It is easily my favourite single player game in a very long time. Partly because of its interesting, but flawed, game-play, but mostly because it has something interesting to say about conflict that has been in my mind since first playing the game.

(Spoiler warning!!! I’m going to be talking about the ENTIRE Three Houses story line in detail. If you have any interest in the game, stop reading now and play this masterpiece for yourself.)

A game about war.

¡Bias warning!

¡Bias warning!

The main quality that sets Three Houses apart from other war games is the subtle ways it communicates both the horrors and complexities of war. A major issue when designing war games is the limitations of the medium itself. Players want to win, and this fact reinforces a very black and white view on warfare that is difficult to get around; there are enemies to defeat, and allies to save. The plot may mess around with the morality of one side or the other, muddy the waters between allies and enemies, by having sympathetic villains, making characters switch sides, questioning the motivations of the hero, or just having the player take side with the villain, but ultimately the final level must have an enemy to overcome and an objective to clear; war is a game with two sides.

At a gameplay level, Three Houses is no different. Similar to how most strategy campaigns allow players to pick opposing factions, players in three houses can find themselves on any of four different routes. However, unlike the typical campaign approach, Three Houses hide the branching of the story from the players until necessary. Players do not need to play through all campaigns to get a complete game experience. During the first half of the game, all four routes follow an almost identical trajectory. The game only significantly branches the story in the second half. As well, the writers were careful enough to only branch when necessary. Certain events are shared across routes, making it possible to experience the same battles from opposing perspectives. Regardless of which faction the player sides with, they still get to be the hero of their own story. However, the interaction between these parallel routes allows us to see biases and complexities that none of the routes individually can express. What we get is a game, fundamentally about war, which is able to express the reality of conflict as more than just two competing sides vying for power.

The titular “Three Houses” refers to the three main student groups at the Officer’s academy. Each house, Blue Lions, Golden Deer, and Black Eagles, represent one of the main political factions on the continent of Fódlan, and are each led by one of the game’s three main protagonists: Dimitri, Claude, and Edelgard. The player character, Byleth a silent protagonist1, is a mercenary recruited by the church of Seiros to teach at their officer’s academy. Early in the game, Byleth is given a choice to lead one of these three houses. The player needs to make this choice before any main plot is revealed, and the consequences of this decision aren’t fully appreciated by the player until much later in the game. Each house is made of eight students and only the mechanical stats and abilities of each ‘unit’ along with a single introductory sentence revealing their personality is revealed to the player before choosing them. The game encourages the player to choose based on little more than its mechanical elements and artistic preference, making the decision feel like a character creation screen. However, this choice turns out to be the most consequential decision in the game.

The game is broken into two main parts. The academy phase, or “white clouds”, is a single narrative viewed through the lens of whichever house you choose. Each month, or chapter, the church sends you and your students on a mission that is common across all routes. As the missions progress, your class tries to prevent an evil ‘Flame Emperor’ and the loosely associated band of cultists ‘Those who slither in the dark’ from interfering in the affairs of the church. The second half chronicles a war that breaks out over the entire land of Fódlan. There are four possible routes that can be taken depending on the choices made in the first phase; each telling a related but different story2.

Mechanics

On no! The creepy librarian was actually evil the whole time.

On no! The creepy librarian was actually evil the whole time.

The game’s mechanics are a big reason why the story of Three Houses works so well. An important part of the fire emblem series as a whole is a mechanic known as permanent death. Unlike other strategy games which might protect playable characters with resurrection items or by returning fallen characters, possibly through an injury mechanic, after the mission is done, dead characters in Three Houses stay dead. Most no longer appear in cinematics, they can no longer be selected for missions, and their story is no longer progressed. Some characters important to the plot might ‘retreat’ from combat, allowing them to fulfill their plot relevant role; however, something terrible inevitably happens to them off-screen once the plot no longer needs them. Notoriously, the game can soft-lock if the player loses too many of their units, especially on harder difficulties, as they will no longer have the resources to clear later levels. Mechanically, death in this universe has meaning, and the plot uses this to great effect.

During the Academy phase, the player spends a great deal of time and effort building relationships with the students. Between each monthly mission you can explore the academy campus and talk to nearly every character in the game, who reacts uniquely to the events of the month. You can offer gifts to students, return lost items, share meals, and even invite them to tea parties. All of these activities build support between you and the students. Support offers a small amount of in game benefit by offering bonuses to units with high support when they fight together, but it is mostly used as a mechanic to further the plot. At certain support thresholds, the game unlocks support conversations where, in a cut scene, students and faculty members share a little about their life and personal struggles. Importantly, you can interact with students outside your house in this way as well. External students can appear as guest characters in some missions, they can offer up quests for Byleth to complete, and, under certain conditions, can be recruited into your house. During the war phase, all students are forced to pick sides in the oncoming war. All characters you recruit side with you, but other characters can find themselves on opposite sides of the conflict. This allows the latter portions of the game to serve up these characters as enemies instead of other faceless minions. Just like how your characters die permanently, characters you face in combat also die when defeated. The act is designed to be emotionally unpleasant, and it is not uncommon to hear of players recruiting as many characters as possible, simply so they won’t be forced to kill them later in the game.

To the level designer who put Bernadetta here: I hate you.

To the level designer who put Bernadetta here: I hate you.

Even background characters are treated like this. Rarely do missions require you to go up against nameless bandits, instead enemies are frequently relatives of one of the playable characters. Chapter three has the player put down a rebellion against the church led by Lord Lonato, the adopted father of Ashe and a student of the blue lions house. Chapter five has the player fight off bandits, led by Miklan, the older brother of Sylvain, another member of the blue lions house, who has stolen a hero’s relic. When playing as any other house, these characters are disposable villains, but to both Ashe and Sylvain these are important life-changing events that colour the story for the remainder of the game. Likewise, the web of noble houses introduced throughout the game means that generals defeated in the war phase are rarely just the monster of the week, but are instead someone’s relative who might have gotten more screen time if the player had sided with a different faction.

All of this works together to create a world where death matters, which adds necessary emotional weight to the war phase of the game. Edelgard reveals herself to be the Flame Emperor, becomes emperor of Adrestia, and declares war on the church of Seiros at the climax of White Clouds. It is here that the game loses its silly and naive video game veneer and transforms into something extremely brutal. Few characters escape death, and death itself becomes the primary driver of the story. In this way, the game escapes portraying the war as just heroic, but also as the tragedy that it really is.

Edelgard’s War: A war to end war.

Edelgard von Hresvelg born the ninth child of Emperor Ionius IX of the Adrestian Empire. In many ways, her story is the story of the Adrestian Empire itself. At a young age she was taken to the Kingdom of Faerghus during a conflict between the emperor and the ruling nobles resulting in a transfer of power away from the Emperor. Upon returning to Adrestia, Edelgard, along with her siblings, found themselves as test subjects in experiments conducted by the cult, Those Who Slither in the Dark, who had at this point deeply embedded themselves in the Adrestian military. They were trying to artificially embed crests, a magical brand that granted the wielder great power, into these children. The emperor, in his much diminished capacity, disproved of these actions, but could do nothing to stop them. Only Edelgard herself survived, making her the de facto heir to the Adrestian throne.

Edelgard’s stated goal in the war is to overthrow a toxic world order. Her upbringing soured her permanently on the idea of crests which she saw as a physically manifested caste system. Those who have crests wield power, both physical and political. Crest bearers can wield ancient and powerful weapons, known as hero’s relics, while those without crests are driven to madness and can be transformed into giant abominations by those same weapons. Normally crests are inherited genetically, and Fódlan’s noble families are defined by them. The nobles engage in aggressive breeding practices to create children who bear crests so that they can go on and lead the family into the next generation. Those without crests, even those from the nobility, form a permanent underclass. Noble children without crests often find themselves viewed as lesser to their siblings in the best of cases and frequently outcasts in their own family. Everyone else is commoners or peasants.

Edelgard sets her sights on the church of Seiros because it is the source of stability to the crest system. All crests find their origin in the founding myth of the church Seiros as each crest is linked to the family line of those warriors who aided Seiros in defeating the King of Liberation long ago. It is the church that perpetuates and maintains the entire system. The church sits at the centre of the continent, acts as an intermediary in political disputes between the three ruling powers, and most importantly supports the noble families and their hero relics. This is made clear in chapter five as Miklan, a crestless son of house Gautier, steals the families’ relic. The church’s response is to kill him, retrieve the relic, and return it to house Gautier. Before the system can change, the church must be removed.

Edelgard wishes to see the world free of crests; a world where those with and without crests can interact as equals. As well, she envisions a world free of the church of Seiros; a world where humans determine their own fate free from the interference of a God. She vowed to use the power that she was unwillingly given to bring about this future at any cost. However, Edelgard’s war is as much a civil war as it is a foreign war. Destroying the crest system also involves unseating the Adrestian elite just as much as destroying the church, and as one would expect, Edelgard’s coronation also corresponded with the assassination and removal of these ‘corrupt’ nobleman. However, this purge has one very notable exception: Lord Arundel.

Lord Arundel is Edelgard’s uncle and the second most powerful man in Adrestia. During Crimson Flower, Edelgard’s route, he represents the Adrestian wing of Those Who Slither in the Dark. Edelgard openly dislikes the cult, and many times throughout the game she refuses to be associated with them. During chapter eight, after Byleth stops the cult from experimenting on a village full of civilians, Edelgard, disguised as the flame emperor, tries to distance herself from the actions of the cult.

And yet, she never does. During all routes, even her own, the cult is present at nearly every major battle. The death knight, Edelgard’s vassal, is present during most of the cults experiments in the early chapters of the game, they are present in the chapter twelve attack on Garreg Mach in all routes except Crimson Flower, and most notably they are present in Edelgard’s final stand in the Azure Moon route3. In crimson flower, the cult mostly disappears, but Arundel takes their place, and Edelgard seems unwilling or unable to check his power. He is seen as a necessary evil, and while Byleth never works with them directly, they continue to operate in the background unhindered.

“Their power is essential to us at present.”

“Their power is essential to us at present.”

The most egregious example of the cult’s relationship with Edelgard happens after the battle of Arianrhod chapter sixteen. In this chapter, Edelgard attacks and executes Cornelia, a kingdom mage, who was involved with forbidden crest magic. Notably, in the Azure moon route, Cornelia betrays the kingdom in favour of the Adrestian Empire. In Crimson Flower, Lord Arundel condemns Edelgard for executing the mage because if, “that were the case, would it not have been better to keep her as an ally?” Implying that she was associated with the cult. Lord Arundel then warns Edelgard to avoid such mistakes in the future. Moments later, the entire fortress and both armies inside are destroyed in heavenly flame, a weapon that in other routes is tied to the cult. Edelgard suspects the attack came from Arundel, but orders both Byleth and Hubert to keep this secret to themselves. In the next chapter, she protects Arundel by blaming the destruction of Arianrhod on the church and uses it as further justification to attack the Kingdom capital directly.

“I will be praying. Praying that the Empire will not become another Arianrhod.”

“I will be praying. Praying that the Empire will not become another Arianrhod.”

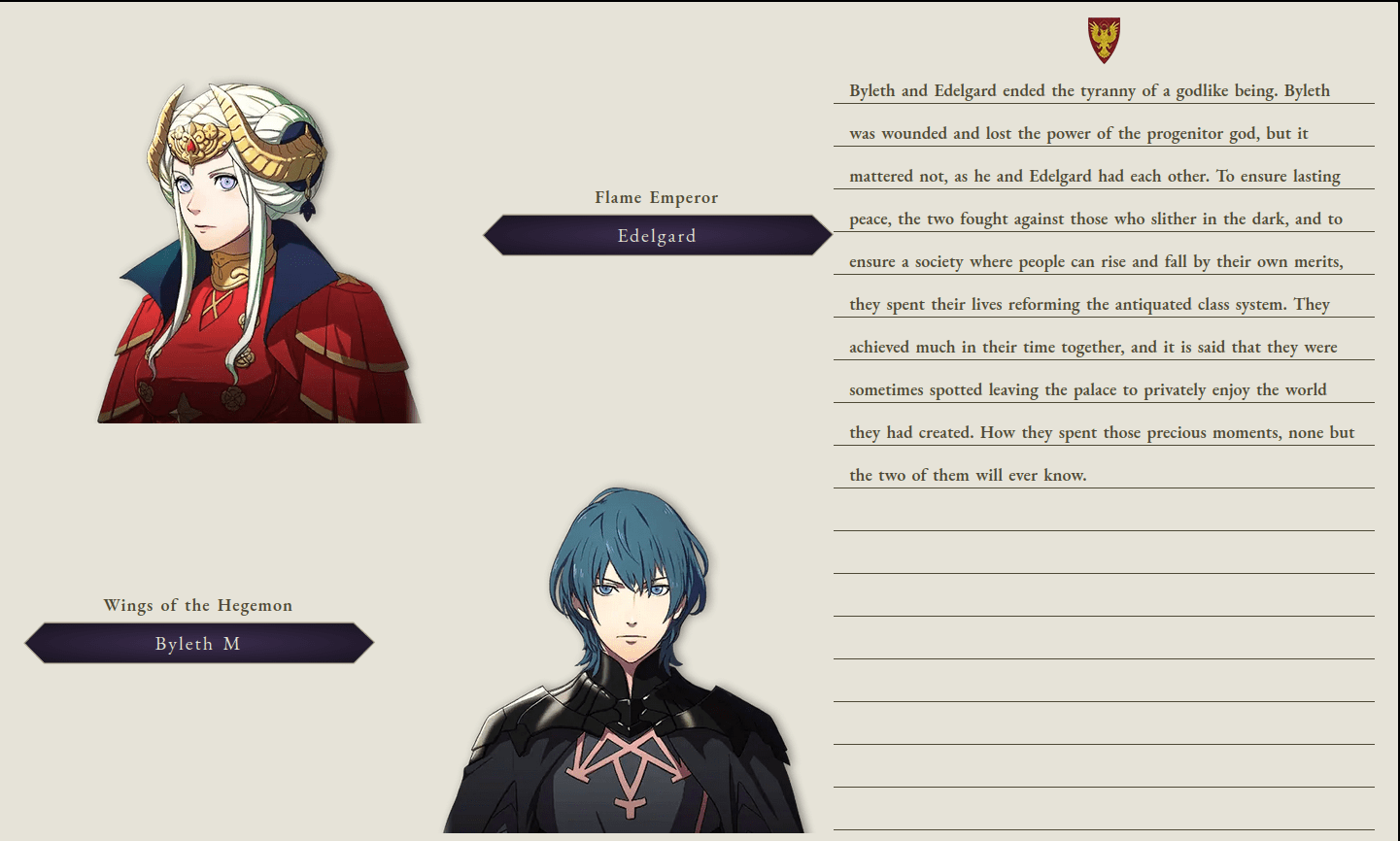

The Crimson Flower route is contentious among the fan-base because it is the shortest route with the least number of missions. It, in many cases, feels lacking and doesn’t do a good job of letting Edelgard tell her own side of the story. Notably, the game ends after Seiros, who in a rage transforms into a dragon and sets the kingdom’s capital, and everyone in it, on fire, is defeated. The fate of those who slither in the dark, to many disappointed fans, is not resolved. While I believe the story could have been better fleshed out, I do believe the omission of the resolution with the cult is on purpose. Many of the epilogues imply that even though the war is over, Edelgard and Byleth continue to fight an underground war against the cult.

Sadly, this is not a screenshot. Had to retrieve this ending from a fan site.

Sadly, this is not a screenshot. Had to retrieve this ending from a fan site.

It is hard to believe that Arundel would have gone quietly, which implies that this underground war is just a gentle way to label a much larger civil war. But the bigger question is what a “world where people can rise and fall by their own merits” actually looks like. Edelgard made it clear that her own feelings on the subject were secondary to her actions. Neither her friends, her enemies, nor her own doubts could convince her to part from her chosen path, and anyone who got in her way wound up dead. Her actions tell a story much stronger than her stated goals. Merit, in Edelgard’s world, is just a pseudonym for useful. The cult isn’t allowed to exist because they deserve it, they are ignored because they are useful. It’s doubtful Edelgard could just suddenly turn off such a fundamental part of her personality, even in peacetime. The above epilogue (There are several depending on how the player ships various characters) implies a happy ending, but it is left unsaid how they go about fixing the issues with society beyond just saying that they did. Yet this is just to prevent reality from spoiling Edelgard getting to be the hero of her own story. She has already set the precedent that her way to a better world is through the corpses of those in her way, and that she is willing to cooperate with evil so long as it’s useful. Why would she ever let anybody undo that victory? So she does create a better world, one where people who agree with Edelgard can prosper, and everybody else likely met the same fate Dimitri did.

Dimitri’s War: Kill every last one of them.

There are no heroes in war; Dimitri is no exception. Dimitri is the eldest son of King Lambert, and the legitimate heir to the throne of Faerghus. His life’s story, however, begins with a single historical event known as the “Tragedy of Duscur.” During his childhood, the royal family was attacked and murdered while on a diplomatic mission to the nearby land of Duscur. Dimitri was the only survivor. Helped by an existing prejudice against the people of Duscur, the ruling nobles in Faerghus blamed the Duscur people of regicide and initiated a genocidal war of vengeance. Most of the population was exterminated, and what little remained of Duscur’s land and people were forcefully incorporated into the Kingdom of Faerghus. Dimitri himself did not blame the people of Duscur for the attack, but found that he, even in his role as the crown prince, could do nothing to prevent or stop the violence. Instead, he found what little salvation he could by interfering with the attack on a single Duscur citizen saving the man’s life. Survivors’ guilt and the knowledge that whoever plotted the death of his family had gotten away with it would plague him for the rest of his life.

Dimitri’s main character arc is defined by his emotional struggles and mental illness. In contrast to Edelgard, he has no internal model of the world that he is building off. He instead reacts to events as they are coming at him. Because of this, he doesn’t really stand out as a character at first. During the first half of the game, he presents himself as a prim and proper royal boy; polite, reserved, and only just a little bit cynical about the role of nobility in the world. Most of his characterization is presented to us through other people. Byleth’s and Dimitri’s interaction with Felix stand out the most. Felix is constantly referring to Dimitri as a “wild board” or a “beast” which should be locked up for everyone’s protection. At first this seems out of character as it clashes with Dimitri’s polite and reserved presentation. However, as the game progresses, we get to see more and more of Dimitri’s dark side. As Those Who Slither In the Dark make their presence known, it gets progressively harder for Dimitri to keep his emotions in check. When he doesn’t, he is constantly apologizing for letting his anger, and his emotions get the better of him.

It is only when Edelgard reveals herself to be the Flame Emperor that Dimitri snaps and loses whatever little control remained over his emotions. At that moment, Dimitri’s world reached a level of clarity it had never reached before. He decides that Edelgard is personally responsible for everything: for Lonato’s defiance of the church, for Flayn’s kidnapping, for the magical experiments at Remire, for Jeralt’s, Byleth’s father, death, and most importantly for murdering Dimitri’s father and adopted mother during the tragedy of Duscur. Edelgard denies this, but the denial is rejected out of hand by Dimitri, “It was foolish to think I could reason with a lowly beast.” Yet, as Felix predicted earlier, it is not Edelgard who is the beast here, it is Dimitri. The final few chapters of the academy phase depict several of his failed attempts to kill her, and as those failures stack up even Dimitri comes to internalize his own beast-like mentality. Eventually, Dimitri’s own kingdom turns on him, and the opening chapters end with a world that believes he was executed.

The Dimitri in the war phase is very different from the Dimitri of the academy phase. Upon reuniting with Byleth, after the five-year time skip, Dimitri is a shadow of his former self. We find him held up in the monastery, violently executing Adrestian officers and lowly bandits. Still hell-bent on killing Edelgard, but without any plan of action beyond marching up to her and punching her head off. The first chapters of part 2 include no character development from Dimitri and very little interaction. He spends the entire time talking with nobody, none of his supports progress, his skills cannot be trained, he does not join in any of the monastery events. He projects power and brutality, yet he himself has none. Byleth, not him, has control of his army. His friends and subjects limit what he can and cannot do. He is little more than a Ghoul who seeks vengeance for the pain and suffering Edelgard’s plan has brought to the world. It is only after the bloodbath of chapter seventeen that he finally snaps out of it.

He’s not lying.

He’s not lying.

Chapter seventeen, The Blood of the Eagle and Lion, is the thematic core of the game. It is a reenactment of chapter seven which is itself a reenactment of a historical battle. Each year, at the academy, the students reenact a war between all three of Fódlan’s political powers. At first, this battle is a ‘mock battle’ and the death mechanics of the game are temporarily put on hold. It is a sporting event that symbolizes the peace that has prospered between the powers since that destructive war long ago, and demonstrates the church’s role in maintaining the peace since then. After the initial battle, the three houses are seen partying together representing their unity. Chapter seventeen is the same battle over again, but the death mechanic is stretched to its limit. It is by far the bloodiest chapter of the entire game, and canonically represents the final chapter for at least a third of the student body regardless of who you side with4.

From Dimitri’s perspective, the story of the eagle and lion begins after chapter fourteen when Dimitri captures an officer of the Adrestian army, Randolph, and threatens to torture him to death. Byleth prevents this by killing the officer and denying Dimitri his fun. Randolph’s sister, Fleche, vows revenge on Dimitri. During the events of chapter sixteen, Fleche is allowed to join Dimitri’s army because she desires revenge, and this desire appeals to Dimitri’s own desire for revenge. However, Dimitri is unaware that Fleche wants revenge on him. As a result, Fleche is allowed to intercept and murder messengers sent to Claude, which fuels Dimitri’s distrust for Claude resulting in a three-way bloodbath between the three houses. After the battle, Fleche attempts to assassinate an emotionally defeated Dimitri. Fleche is prevented from Killing Dimitri by Felix’s father Rodrigue at the cost of his life.

The thing that finally wakes Dimitri up from his emotional slumber is the thing that put him in it in the first place: Dimitri’s empathy. He feels the suffering and emotions of the people around more than he feels his own emotions. Yet he cannot reconcile these feelings with the reality of the world around him. He ‘hears the voices of the dead’ and seeks justice for those who have been wronged; yet it is only on Gronder field at the battle of the eagle and lion that he wakes up to the reality that his pursuit of justice is itself an injustice. He blames Edelgard for the death of his family, yet she wouldn’t have been much older than he was at the time and likely would have had no say in how it went down even if she was involved. Likewise, Randolph’s only crime was fighting in a war he had no say in starting. Fleche sought justice for her family just as Dimitri sought justice for his, and neither would find resolution in the death of the other. Instead, both simply contributed to the endless cycle of violence. Earlier in the game Dimitri would say to Byleth, “I wonder which is best, Professor… To cut away that which is unacceptable, or to find a way to accept it anyway…” I believe that it is only after Gronder that this question was answered. The Tragedy at Duscur would always be with him, and no amount of cutting could ever remove the injustice from his life. His only option was to accept that which has happened, and to focus on those who remain alive instead of seeking endless and meaningless retribution for those who are gone.

After the battle, a transformed Dimitri reclaims his throne, restores his relationship with Claude, and battles Edelgard back to her throne room. His focus is no longer on causing Edelgard pain, but instead ending a violent and brutal war. During her final stand, Edelgard allows herself to be transformed into the Cult’s crest weapon ‘Hegemon Husk’, and the two engage in one final battle. After a long and gruelling battle5 Edelgard is defeated and the war finally ends. Victory, however, is not cast as victorious but tragic. During the final cinematic, a defeated Edelgard sits before Dimitri expecting death. Instead, Dimitri wordlessly offers her a hand instead, she replies by throwing the dagger Dimitri had given her as a child when she was visiting Faerghus; she wants nothing to do with Dimitri’s future, and the war cannot end while Edelgard lives. After stabbing her through the stomach, Dimitri removes the knife from his shoulder and leaves it with her before walking with Byleth out of the room. Right before exiting, Dimitri empathetically looks back at Edelgard, but Byleth grabs him and pulls him through the door; his responsibility is to the living, not the dead.

Conclusion

The problem with stories like this is that it is always easier to demonstrate all the wrong ways to change the world than it is to demonstrate the right way. What makes Edelgard such a great villain is that she so remarkably represents everything we are taught to value in an individual: she is strong, decisive, driven by a vision powered by something she firmly believes in, she is unemotional and chooses not to be driven by them. All of her actions are her own, and she accepts both responsibility and credit for those actions. Yet all of these qualities are what makes her a villain. Her refusal to see through the lens of her emotions makes her unable to see the suffering of others. Her focus on goals creates an environment that is tolerant of evil. The only person who sees a separation between her goals and those of the cult is herself. It’s easy to be swayed by her vision of the future as the church is guilty of most of the crimes she condemns them for. The church does rule at the expense of commoners, they do support the crest system, they do violently suppress those who speak out against them, yet this desire for a better world does not create one. Instead, her inability to see through any eyes except her own makes her become that which she hates the most. During her final hour, she embraces the power of the crests, and transforms into the Hegemon Husk, a crest powered beast, exactly as Rhea does in her final hour. The crimes of the church do not excuse the death she brings to the world through war. It is her war as she is the one who decides that death is the only way forward; it is only through her death that the war really ends.

“I believe I have chosen the best path, the only path.”

“I believe I have chosen the best path, the only path.”

I do think that there are some lessens that the characters come to understand about how we interact with a corrupt society. Dimitri’s story emphasizes the power of empathy over ideology. Dimitri begins the game with a strong sense of right and wrong, but is unable to reconcile that with the world around him because the voices he hears are those that only he speaks for. He refuses allegiance, compliments, and even friendships because he believes he doesn’t deserve them. Likewise, he seeks justice for people who never asked for it. His redemption comes because he starts to listen, he liberates Faerghus before eliminating the empire because that is what his people are asking for, he rescues Claude because Claude asks for it, and finally he kills Edelgard, not because he wants to, but because she has decided that her war can only end on her terms.

Edelgard’s story emphasizes the need to reconcile action with intention. It’s difficult to take her at her word that she wishes to produce a better world because there is a disconnect between the things that she says and the things that she does. She pretends to be angry at the crest system but instead of focusing her energy against those, like the cult and the ruling lords in Adrestia who weaponize the crest system, that are external and easy to demonize. In this way, she allows the Adrestian Empire to use even her suffering as a weapon against its enemies. In the end, instead of beating the system, Edelgard became the very thing she was always meant to be: a weapon designed specifically to preserve the Adrestian way of life. Edelgard’s story is a demonstration of how worthless good intentions are if the actions associated with those intentions are not focused on solving actual issues.

This isn’t to say that Dimitri’s ending is in some sense a ‘good’ ending. In it, none of the systematic issues with Fódlan are addressed. The tragedy of Duscur is never truly resolved, the people of Duscur are never avenged, the crest system Edelgard abhors still stands, the church still exists, and the cult is neither defeated, nor even implied to have been defeated in his Epilogue. For all intents and purposes, the only winner is the status quo. Yet there is hope as a new generation takes power. Dimitri, now king of Faerghus, goes on to rule a now united Fódlan, and Byleth takes over as the archbishop of the church. Together, these two have tremendous power to shape a new Fódlan. Positive change is not guaranteed, but perhaps a leader willing to listen can push things in a better direction.

If Three Houses has anything to say, it is not that history is written by the victors; instead, history is written by the survivors. The thing that has most successfully stuck with me about Fire Emblem: Three Houses as a game is that it is an admission that war is complicated. It is a tragedy, sometimes necessary, sometimes absurd, sometimes horrific, sometimes heroic, and always a matter of perspective. It is what happens when one worldview decides that it cannot exist alongside another one. It is the collision of two realities travelling at great speed. It is an insatiable flame that births a new world; yet, such a world is rarely what any of the inputs intended.

-

Which means that they are a silent meat puppet designed to act as a self-insert, who communicates through vague gestures and whose only emotional experiences are those that other characters inform us that they are having. ↩

-

These sections are known as: Crimson Flower, Azure Moon, Verdant Wind, and Silver Snow for siding with the Adrestian Empire, Kingdom of Faerghus, Lester Alliance, or the church itself. ↩

-

Although they have no loyalty to her and run away if their leader is defeated. ↩

-

The fact that this chapter is skipped in Crimson Flower is a huge oversight, massive missed opportunity in my opinion. ↩

-

The hardest map in the game in my opinion. ↩